Does the term "rewrite" scare the bejeezus out of you? Good. It should. A rewrite is not something to be taken lightly and should be your very last resort. There are less painful routes you can take, but what if there really is no valid alternative to "The Big R"?

Old versus new

We've all been there. You're the new guy on an ongoing project. You've got high hopes: push-button deploys, code so clean your eyes tear up a little and a fast and maintainable test suite that allows you to safely refactor to your heart's content. Adding new features to this beauty will be a delight!

But then reality starts to creep in slowly. As you delve deeper down the stack you start to notice the dark secrets the codebase hides. Automated tests might not have made it to every corner of the world. The technology the application is built upon is outdated - to the point that staying up to speed with current market trends becomes nearly impossible. As time moves on, features get harder and harder to add. The codebase has started to rot. If not you, then someone on your team is bound to utter the following words in a moment of despair:

If only we had the time to rewrite this mess, all our problems would disappear.

Stop. Right. There. Many teams have gone down that road and almost as many have failed miserably. Some stuff you might consider before going down the rewrite-path:

-

The existing codebase will keep evolving. The maintainers of the old system will fix bugs and implement minor improvements. The rewrite will keep lagging behind the old system.

-

Code is the only place that fully describes the old system's behaviour. No matter how good your requirements documents are, the only place that accurately describes the full behavior of the system -warts and all- is the system itself. All those platform-specific exceptions, all those edge cases are only documented in code. Given the fact that people are pushing for a rewrite, there's a big chance there are no automated end-to-end tests that you could use to verify that the new system works exactly the same as the old one.

-

A rewrite provides no real value to your customer. From a developer's point of view, the value of a rewrite is simple: maintaining the system and adding new features to it will go much smoother. Your developers assure you that this time everyting will be different. The rewrite will allow new features to be implemented much more rapidly. Newsflash: there's a good chance these developers are the same people that created (or at least contributed to) the original mess. They might use a shiny new technology for the rewritten system, but let's be honest: we'll end up in exactly the same situation except that we also gave our competitors a three year headstart.

-

Most of the time, there are cheaper alternatives. More on that further down.

Alternatives to a rewrite

There are alternatives to starting from scratch. Moreover, there are only a few reasons that warrant a rewrite. If there's no external force that prohibits you from cleaning up the mess you currently have, that's exactly what you should be doing: clean up the mess you created.

We should be treating our codebases more like pets.

You don't dump your dog somewhere in the woods and replace it with a shiny new pup just because he's grown some bad habits. As they say: your dog's personality is a reflection of your own. What makes you think the next one will turn out any different? Perhaps all that extra knowledge you have acquired when training the old dog will enable you to get it right this time? Guess what, the old dog is the only place that contains all that accumulated knowledge. It will take a lot of time and effort to teach your new dog all the tricks your old companion has already mastered through hours of training.

This path won't be a walk in the park either, but it'll save you a lot more problems than starting from scratch. Keywords here are: step-by-step redesign/refactoring of the codebase under the safety net of regression tests. This is a field on its own so expect more on this in later posts. For those that can't wait to get started I recommend reading Adrian's posts about legacy code here. Also, grab a copy of Working Effectively With Legacy Code. Keep it on your nightstand. For anyone working with a mature codebase, this should be your new Bible.

When might it be OK to consider a rewrite?

If you have...

- The financial freedom to lower the rate at which you are currently delivering features and/or maintaining the system and

- You are migrating to an entirely new programming language, technology stack or any other force that prohibits you from working from what you have

- Or maybe even completely reimagining your software product

...it might be okay to consider a rewrite from scratch. But weigh your alternatives carefully and don't go in expecting a painless big bang replacement.

Case study: moving from SQL to C#

During my career I came across a single project that in my view warranted a rewrite. Full disclosure: I was the loudmouthed developer insisting on a rewrite that would make everyone's life (but mostly my own) better.

Some context: the application was an atypical three-tier web app. There was a presentation layer that rendered HTML. There was a data layer implemented on a SQL database. Now here's the kicker: there was no typical application tier. The "application" tier was a single webservice operation that translated HTTP requests to stored procedure calls on the database. Both input and output for these stored procedure calls was custom XML. I'll give you a few moments to collect yourself.

High-level architecture of the legacy application.

Back? Okay, on with the story. The symptoms we faced as a development team that led us down the path of a rewrite:

-

Everything was custom-made. It took new developers a year to get comfortable with the system's architecture.

-

The existing codebase was huge for what it was doing. Literally hundres of tables and thousands of HTML pages supported a mainly CRUD-flavored frontend.

-

The application was mainly written in SQL. Not every developer is a SQL whizkid so staffing was a permanent issue.

-

SQL provides little to no abstraction mechanisms. You can write custom functions, views and stored procedures but that's nowhere near the flexibility a full-fledged OO language gives you. Combine this with the fact that the system had no automated tests whatsoever and that each use case was implemented as a single (enormous) stored procedure, refactoring this baby would have resulted in a painstaking exercise.

-

We were asked to create a "lightweight" version of our system that required both tweaks in UI and backend logic. Rather than uglifying the codebase even more, this was the final trigger that pushed us in the direction of the rewrite.

Strangling a legacy system

If at this point you're still convinced that your application warrants a rewrite, read on:

From the outset we made the choice to move away from the current architecture. No more ad-hoc XML getting pushed to the browser that was tightly coupled to a handrolled javascript framework. No more business logic in the database. Instead we opted for a modern programming language that allowed for a higher level of abstraction and easier testability than SQL and allowed us to leverage industry-standard frameworks like ASP.NET MVC and testing support from day one.

Our approach closely resembled what Martin Fowler calls a Strangler Application. The trick is to incrementally develop the new system while gradually replacing the old one. No big bang approach, but frequent releases. That means keeping both systems deployable at all times. As the functionality of the new system grows, it can slowly take over functionality of the legacy system and slowly strangle it out of existence.

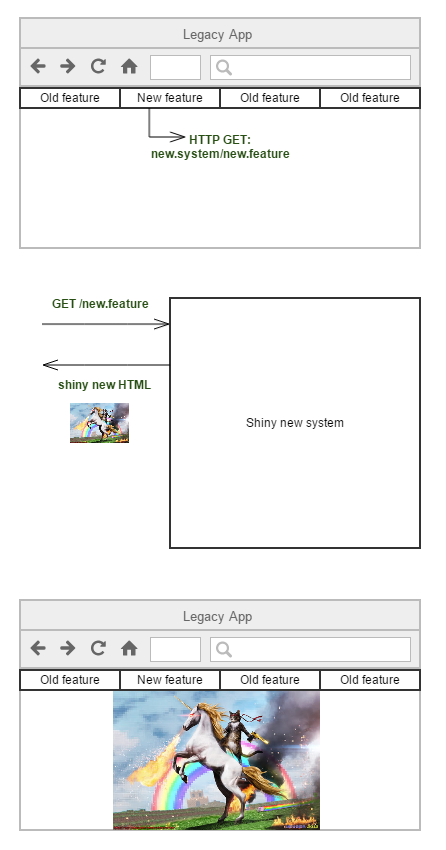

Determine integration points between old and new

At some place in your architecture you will have to place a routing point that will forward requests for new behaviour to the new system and stuff that hasn't been moved yet to the legacy system. If you are replacing a legacy web app at the level of HTTP requests, it can be as simple as pointing requests for new functionality to the address of the new system and keep routing old functionality to the legacy system.

In our case we decided to replace the front-end as well, as we did not want to drag along the custom framework any longer. This meant that we needed some way to integrate the new UI inside the old web app. We ended up writing a client-side router that loaded the new app HTML inside a div in the legacy application's UI whenever new functionality was requested. Once the new HTML was loaded, users could interact with the new system freely.

Routing new calls to the new system and rendering the new UI inside the legacy app.

On the other end we had to integrate with the data layer of the old system as well. If you can separate the data layer between both systems by any chance, do it. Allowing multiple applications to simultaneously read and write to a single database can lead you down another painful path of deadlocks and other general unpleasantries.

Lessons learned

Create a proof-of-concept as soon as possible. Until you have a hybrid setup running in production, a lot of problems will remain undetected. Release early, release often.

Maintaining a hybrid system is complex. In the timeframe where both the new and the legacy system are running next to each other, development and operations have to maintain and understand two applications. Not only do they have to understand each system seperately, they have to understand all the intricacies of how they interact with each other. This is a painful situation you want to get out of as soon as possible.

Don't invest further in the legacy system. When a new feature request arrives, try to implement it in the new system. It might seem tempting to push it into the legacy app because that would require "less work". This will lead you down the path of eternally maintaining a hybrid system. On that way, madness lies.

Keep the original development team involved. It might seem tempting to assemble a new "tiger team" to implement the new system. After all, the previous developers screwed up the legacy application, didn't they? Don't. This is bad for morale and creates an us-versus-them tension. You need those developers to get a better understanding of the legacy system they worked on for years and you might need them to maintain the new one after the tiger team leaves for greener pasture.

Do it right the second time around. Don't go down the same road with the new system. Make the new system testable from the start. Better yet, bite the bullet and test your system from the start. When developing a proof-of-concept it might be tempting to just "hack it together", but these things have a habit of growing into a big mess rapidly. As you learned the hard way with your old system, code turns into "legacy code" before you know it. Just save yourself the trouble and write clean code from the get-go. Before you commit new code, unit test the heck out of it (or maybe try writing the tests before you write the production code!). Cleanly separate concerns. In other words: make the new system easy to strangle.

Conclusion

In case I have not made myself abundantly clear: a big rewrite will cost you more than you bargained for. There is no guarantee the new system will result in an improved situation. Every greenfield effort starts with high expectations and most of them are unable to hold up to their initial ideals. It might be economically more interesting to work from what you have and incrementally massage it into a more maintainable solution rather than throwing it all away and starting over. When you do rewrite from scratch, opt for an incremental approach that gradually replaces the legacy system and always provide a fallback scenario if things turn out to be even more expensive than you anticipated. Finally, try to learn from past mistakes. Build it right this time around.

Are you currently experiencing the pains of a legacy codebase and have no idea on where to start improving? Are you demanding/currently involved in a big rewrite? I'd like to hear from you! Leave a comment below or contact me at @jovaneyck.

Further reading

There's a whole library worth of literature regarding this topic. Here's a list some of the references I appreciated when deciding to go for our own rewrite.

-

Joel Spolsky wrote about rewrites in Things You Should Never Do. The article's name alone is a dead giveaway.

-

The big rewrite by Chad Fowler. This guy faced his fair share of rewrites so you should check out his experiences if you are considering a rewrite.

-

How to survive a Software Rewrite by James Shore. Discusses "the five stages" of a software rewrite. Funny if you aren't currently living the nightmare.

-

A concrete strategy to rewrite a component of your system while still continuously releasing your product can be found at Make Large Scale Changes Incrementally With Branch by Abstraction. Must-read for anyone considering the strangler approach!

-

David Heinemeier Hansson from Ruby-on-Rails fame wrote up a succesful rewrite here. Punchline: if you currently have a chair and you want a new table, restarting from scratch is a viable (the best?) option.

-

Several case studies of the Strangulation approach can be found here.

Featured image by Elixism.

Like this Blog?

Then you’re in for a treat! Visit Jo Van Eyck's personal blog, which offers many more hours of excellent reading material!